Five Costly Mistakes Foreign Companies Make When Entering India – A Delhi NCR CA Perspective

India is one of the most attractive destinations for foreign investment, with a large consumer base, strong talent pool and a reform‑oriented government. Yet many foreign companies still struggle in India—not due to lack of opportunity, but because of avoidable structural and compliance mistakes at the entry stage.

For foreign investors setting up in Delhi NCR (Delhi, Gurugram, Noida, Greater Noida), choosing the right structure, ownership model and governance framework on Day One often makes the difference between a smooth scale‑up and a painful clean‑up.

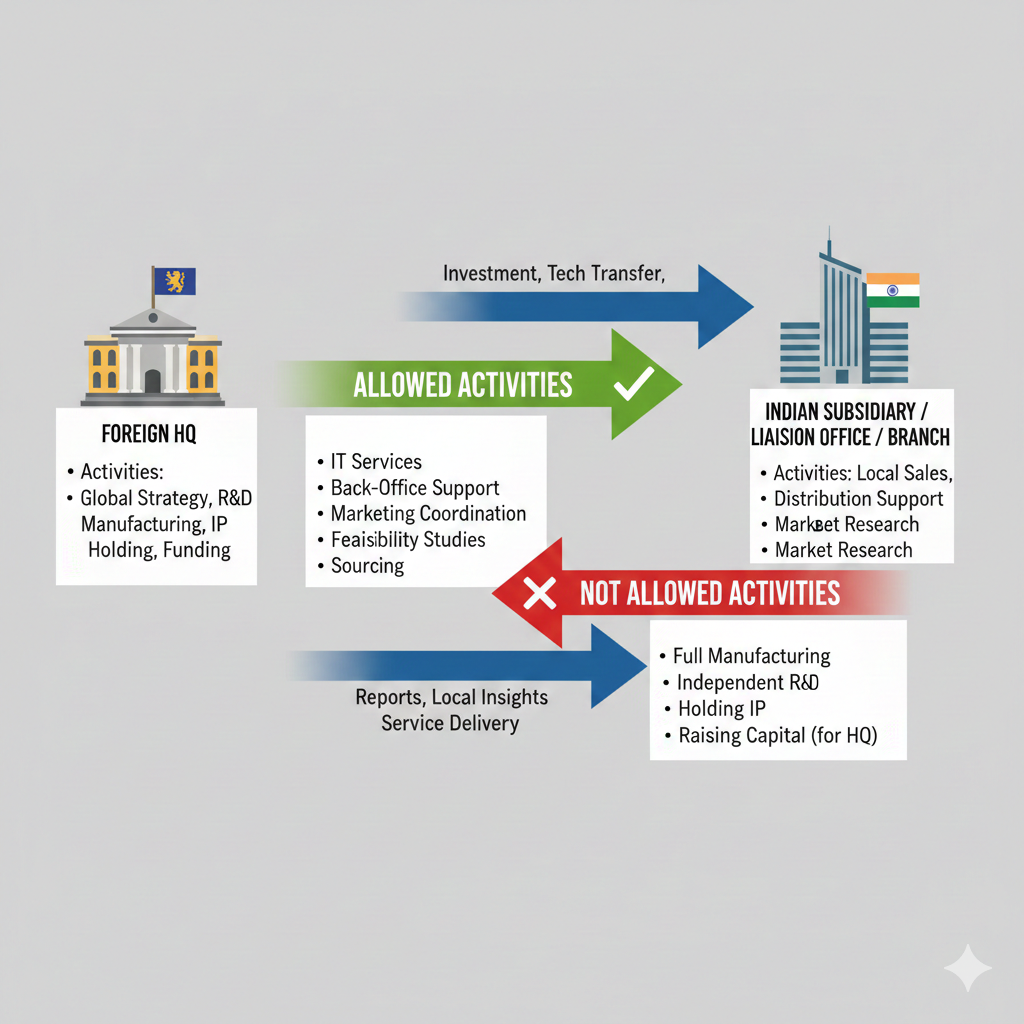

Mistake 1: Choosing the Wrong Entry Structure

India offers multiple entry options under FEMA and RBI regulations, each with clear limits on what you can and cannot do.

Common India Entry Structures

| Structure Type | Key Purpose / Limitation |

|---|---|

| Liaison Office | Communication & representation only; no revenue, contracts or invoicing allowed. |

| Branch Office | Limited commercial operations aligned with parent’s activities; subject to RBI approval. |

| Project Office | Set up to execute a specific contract or project in India. |

| Wholly Owned Subsidiary (Pvt Ltd) | Full commercial operations, invoicing, contracting, hiring, and scalability. |

A frequent mistake is setting up a Liaison Office and then informally using it for business development, negotiations, or even billing. A Liaison Office is legally barred from commercial activities; mis‑use can trigger violations under FEMA and RBI regulations, exposure to taxes, penalties, and even forced closure.

Practical Takeaways

- If you intend to invoice Indian customers, sign contracts, employ staff or book profits in India, a Private Limited Company (wholly owned subsidiary) is usually the most robust option.

- Liaison and Project Offices should be used only where the scope genuinely fits their limited mandate.

Example

A European tech company opens a Liaison Office in Gurugram to “test the market,” but allows Indian staff to negotiate prices and sign MoUs on letterhead. Over time, tax authorities and RBI may treat this as a de facto permanent establishment, exposing the group to back‑tax, interest and penalties.

Mistake 2: Ineffective Ownership Structuring

How you hold shares in your Indian entity has implications for control, tax, funding and exits.

What Often Goes Wrong

- Shares initially allotted in the personal names of local directors to “speed up” incorporation.

- Foreign individual shareholders holding equity directly, instead of the foreign parent.

- No alignment with the group’s global holding and IP structure.

This can lead to:

- Governance bottlenecks (you need individuals to sign off on actions).

- Complications during capital infusion, ESOPs, M&A or internal restructuring.

- Misalignment with global transfer pricing and substance planning.

Better Approach: Route Through the Foreign Parent

Where feasible, the Indian company should be owned by:

- The foreign parent company or

- A designated global holding company, in line with group structure and tax treaties.

This provides:

- Clear strategic control in HQ.

- Simpler implementation of group‑level policies.

- Easier due diligence for future investors or buyers.

FDI Route Considerations

India’s FDI policy differentiates between:

| FDI Route | Requirement | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Automatic Route | No prior approval | Up to 100% foreign ownership in permitted sectors. |

| Government Route | Prior approval required | Approval and sometimes Indian partner needed. |

Understanding the applicable FDI route for your sector (e‑commerce, fintech, media, defence, etc.) is crucial before finalising shareholders and capital structure.

Mistake 3: Unbalanced Board Composition and Governance

Every Indian company must have at least one resident director. Many foreign subsidiaries mechanically appoint one resident director and one foreign director without thinking about control and continuity.

Common Issues

- Only one resident and one foreign director – creating ambiguity in control and difficulty in decision‑making.

- Delay in obtaining Director Identification Number (DIN), Digital Signature Certificate (DSC) and KYC, leading to delays in MCA filings.

- Resident director treated as a mere signatory with no clarity on responsibility.

More Strategic Board Composition

A more balanced approach is often:

- Two foreign directors (representing HQ) plus one resident director.

- Clearly documented roles and decision‑rights in the Articles of Association and supporting board protocols.

This ensures:

- HQ retains commercial and strategic control.

- Local governance and compliance are properly handled through a trusted resident director.

Mistake 4: Underestimating India’s Regulatory Landscape

Many foreign companies comply with one law (e.g., Companies Act) and inadvertently miss others, leading to fragmented compliance and risk.

India’s Multi‑Layered Compliance Regime

Key regulatory layers include:

- Companies Act – incorporation, board meetings, annual returns, filings.

- FEMA & RBI – FDI reporting, share allotment, external commercial borrowings, liaison/branch reporting.

- Income‑tax – corporate tax, TDS, transfer pricing documentation and reporting.

- GST – registration, invoicing, periodic returns, e‑invoicing and e‑way bills where applicable.

- State labour & commercial laws – Shops & Establishments, PF, ESI, professional tax, etc.

Many foreign entrants:

- File ROC forms but miss FEMA reporting on share subscription.

- File income‑tax returns but ignore transfer pricing documentation or international transaction reporting.

- Take GST registration but do not align contracts and invoicing structures with tax positions.

Best Practice – Centralised Compliance Calendar

For a foreign company entering India, a single‑window compliance view is essential:

- Create a consolidated calendar covering MCA, FEMA, Income‑tax, GST and labour laws.

- Engage an India advisory partner (CA/CS firm) to monitor due dates and handle filings centrally.

For Delhi NCR operations, this becomes even more important due to multi‑location offices (Delhi, Haryana, UP) and state‑specific registrations.

Mistake 5: Ignoring Documentation Protocols

India remains documentation‑intensive, especially for foreign stakeholders.

Frequent Documentation Gaps

- Foreign documents not apostilled or notarised as per Indian requirements.

- Documents in non‑English languages without certified English translations.

- Using documents older than 3–6 months when fresh ones are required.

- Missing board resolutions or identity/address proofs for authorised signatories.

These issues delay:

- Incorporation approvals.

- PAN/TAN/GST registrations.

- Bank account opening.

- FDI reporting and share allotment.

Practical Documentation Checklist

Before you start incorporation:

- Collect and apostille/notarise: Certificate of Incorporation, Memorandum/Articles of foreign parent, authorised signatory resolutions, KYC of directors and shareholders.

- Ensure documents are recent (within 3–6 months, as required).

- Prepare certified English translations where originals are in another language.

A well‑prepared documentation pack can shorten your India set‑up time by several weeks.

Key Takeaways for Foreign Companies Entering India

- Choose the right structure – Subsidiary vs Liaison vs Branch vs Project Office should follow business objectives and FEMA limits.

- Plan ownership properly – Prefer institutional (parent‑level) ownership over individual names; align with FDI rules.

- Design the board deliberately – Ensure a compliant but control‑oriented mix of foreign and resident directors.

- Respect the regulatory stack – Integrate Companies Act, FEMA, Income‑tax, GST and labour compliance into one view.

- Over‑prepare documentation – Apostille, notarisation, translations and updated KYC are non‑negotiable.

FAQs – Foreign Companies Setting Up in India

1. What is the safest entry structure if we want to do full business in India?

In most cases, a wholly owned subsidiary (Private Limited Company) is the most flexible and compliant structure for operating, invoicing, hiring and raising local capital, subject to sectoral FDI conditions.

2. Can we use a Liaison Office to “test the market” and later convert it into a subsidiary?

A Liaison Office can only undertake communication and representation, not revenue‑generating activities. You may later incorporate a subsidiary and transition operations, but activities carried out through the Liaison Office must strictly remain non‑commercial.

3. Should shares of the Indian company be in the names of local directors?

As a rule, no. Ownership should be vested in the foreign parent or group holding company, not in individual directors. Using individuals creates governance and exit risks.

4. How long does it typically take to set up a subsidiary in Delhi NCR?

If documentation is complete and properly apostilled/notarised, and name/FDI conditions are straightforward, incorporation and basic registrations can often be completed within a few weeks. Delays usually arise from documentation gaps or FDI sectoral nuances.

Disclaimer

This blog and the accompanying posts are general informational content based on publicly available material and do not constitute legal, tax or investment advice. The applicability of any structure or compliance requirement depends on the specific facts, sectoral regulations and subsequent changes in law. Readers should seek professional advice from a qualified Chartered Accountant or legal counsel before taking any action.